When the bass steps into the spotlight

At the Palm Springs International Jazz Festival, an instrument long consigned to the background becomes the through line of a century of jazz history — from New Orleans parades to fusion, funk and the future.

Giving bass players nightly top billing at a music festival is like putting a slab of cement on the cover of Architectural Digest; like putting Tiger Woods’ caddie on a box of Wheaties; like writing a song about the guy who catches the daring young man on the flying trapeze.

But that’s what the Palm Springs International Jazz Festival is doing at its Feb. 20-22 event following a Feb. 19 twilight reception at the Franz Alexander mid-century modern home.

Local reporting and journalism you can count on.

Subscribe to The Palm Springs Post

Stanley Clark, perhaps the first bass guitarist to become a jazz star, will headline its opening night with his N4Ever band at the Palm Springs Art Museum’s Annenberg Theater.

The Preservation Hall Jazz Band, led by upright bassist Ben Jaffee, will get the 8 p.m. marquee slot the next night at the Plaza Theatre to showcase the trad jazz that emerged in the early 1900s in New Orleans.

Singer-bassist Esperanza Spalding, the first jazz artist to earn a Best New Artist Grammy in 2011, closes the fifth “not-quite-annual” event at 8 p.m. Sunday at the Plaza.

The festival also features blues-based pianist Ben Sidran, Brazilian singer-pianist Eliane Ellis, and former Rolling Stones backing vocalist Lisa Fischer in a jazz bass showcase from the oldest, most rudimentary styles to modern, subtly sophisticated approaches.

In fact, so many important marks on the bass evolutionary scale are depicted, a scholar like Idyllwild Academy of the Arts jazz instructor Marshall Hawkins could conceivably assemble a timetable of jazz styles with just a few links missing from the festival lineup.

“There’s a lot of missing links,” said Hawkins, who played bass for Miles Davis, “and I don’t know them all.”

But Hawkins not only knows the milestones of the jazz bass evolution, he was literally there when the great Miles led one of its most dramatic paradigm leaps.

Hawkins toured with Davis in the late 1960s after Miles began thinking about replacing his “Second Great Quintet,” featuring pianist Herbie Hancock and bassist Ron Carter. For Miles’ second recording session for his 1968 release, “Filles de Kilimanjaro,” he used a unit led by keyboardist Chick Corea, launching Davis’ transition from post-bop to fusion jazz.

Acoustic bassist Dave Holland replaced Carter at that recording session and for his 1969 release of “In A Silent Way.” But Holland then made history by playing on Miles’ landmark fusion LP, “Bitches Brew,” with bass guitarist Harvey Brooks.

Brooks had played electric bass for Bob Dylan’s classic “Highway 61 Revisited” LP and The Doors “Soft Parade” album, featuring “Touch Me.” So, the two bass players on “Bitches Brew” represent a true fusing of jazz and rock, and Holland could credibly be called the missing link between Clark (who got his break in Corea’s Return To Forever band), and Paul Chambers, who was Hawkins’ primary bebop influence.

After missing the opportunity to be that missing link, Hawkins transitioned into academia.

“He replaced me in Miles’ band,” Hawkins said of Holland. “I may have missed that (“Bitch’s Brew”) recording. I was in Washington, D.C. When I got back to New York, Miles said, ‘I was looking for you, Marshall. I was wanting to do a recording.’ Well, I’m gonna tell you point blank. I’m glad I missed it. Because I wouldn’t be talking to you now.”

Hawkins, a spry 86-year-old, doesn’t claim to be a historian who can discuss Ben Jaffe’s influences on upright bass. But Jaffe’s father, Preservation Hall Jazz Band founder Allan Jaffe, played trad jazz on tuba, and Hawkins will say the bass succeeded the tuba after America’s original art form transitioned from parades to venues like Preservation Hall.

“They’re one and the same,” said Hawkins. “Different in terms of instrumentation, but they’re the same in terms of its responsibility in the music. I’ve heard tubas who play walk (a steady quarter-note rhythm with an ascending and descending melody). The bass walks, too. So, it’s all relative. The bass is just more subtle. The bass has a lot of air. The tuba moves even more air. It’s louder.”

The first famous New Orleans bassist, to whom Ben Jaffe could trace his musical lineage, was Pop Foster, who was doing slap bass solos in New Orleans and on riverboats before joining the King Oliver and Louis Armstrong bands in the 1920s and ’30s.

“He knew how important the bass was and that’s why he was famous,” said Hawkins. “He didn’t miss notes. He was invisible. He was so invisible that he’s in our history.”

In the “Jazz Age,” as the 1920s were called, most popular white bands used stock arrangements provided by New York music publishers. So, the bass playing was rather uniform. But in heavily Black areas such as Harlem and Chicago’s South Side, Black bandleaders like Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson created unique charts and hired arrangers, like the white “King of Jazz,” Paul Whiteman, did with Ferde Grofe. That soon inspired white bandleaders like Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey to launch the Swing Era, where every major big band had arrangers creating original orchestrations.

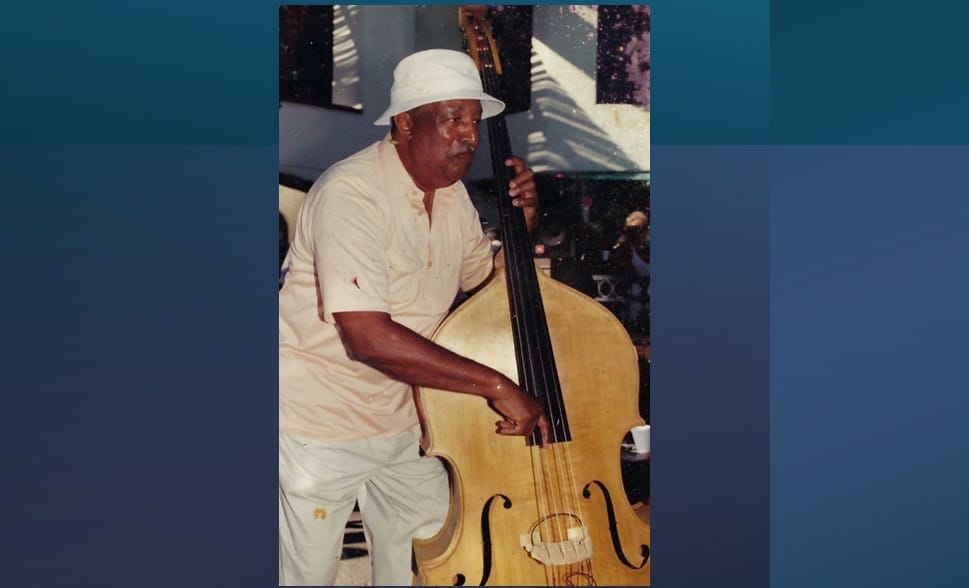

Milt Hinton, whose career stretched from the Cab Calloway Band in the Harlem Cotton Club in the 1930s to jazz parties in Palm Springs in the 1980s, was a notable transitional bass player from trad jazz to swing. But the bassist who created the most evolutionary change was Jimmy Blanton, who played for Ellington’s heralded big band of 1939 and ’40, featuring Palm Springs legend Herb Jeffries on vocals.

“Jimmy Blanton was amazing,” said Hawkins. “I think he could have been the leading edge of recorded bass solos. But there were people in there long with him.”

One was Ray Brown, who began playing with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Bud Powell on the first day he arrived in New York from Pittsburgh in 1945 at age 21. He had a rare jazz hit with his composition, “One Bass Hit,” with Gillespie’s 1946 band. That led to a high-profile tour with Jazz at the Philharmonic and a short marriage to Ella Fitzgerald, making him the most famous Black bass player of the bebop era. His influence on younger jazz musicians was felt into the 21st century — especially in Los Angeles, where he was acknowledged as its jazz godfather. He played every Jazz Celebrity Golf and JAMS Session in Palm Desert from 1997 until four months before his death in 2002.

Hawkins called Brown, “Star Wars.”

“He was just one of a kind,” he said. “Ray Brown has a following. So you have to put Ray Brown in there.”

But Hawkins was more impressed by bassists like Chambers, who played with Miles on “Kind of Blue,” Charles Mingus and George Morrow, featured in the Clifford Brown–Max Roach Quintet in the mid-’50s.

“Ray Brown is definitely not one of my influences,” he said. “Paul Chambers, Mingus, even people like Eddie Gomez. Mingus stands by himself. I say Mingus among us. I think Jimmy Garrison (John Coltrane’s longtime bassist) for sure. He’s between Paul Chambers and Butch Warren (Thelonious Monk’s bassist in the early ’60s).”

Clarke, 74, was from the next generation. He came up as Jimi Hendrix and Sly and the Family Stone were inspiring Miles Davis. Clarke was as influenced by Sly Stone’s slap bassist, Larry Graham, as he was by Ron Carter. His title song from his 1976 funk fusion LP, “School Days,” was as popular as Brown’s “One Bass Hit.” He played upright bass on his first solo album, “Children of Forever,” with Dee Dee Bridgewater on vocals. But, in 1979, he rocked with the New Barbarians, featuring Keith Richards, Ron Wood and Bobby Keys of the Rolling Stones and Zigaboo Modeliste of the New Orleans funk band The Meters.

“He seems pretty phenomenal,” said Hawkins. “Could be the guitar. The electric bass is a different instrument. But he developed and evolved playing the upright bass.”

“She’s a genius. Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, all of these people, that’s already been done. Find something else to do. Spalding, she’s a genius because she’s chosen a way to go that nobody’s done before.”

— Marshall Hawkins, on Esperanza Spalding

Hawkins puts Clarke in a genre with Jaco Pastorius, who broke boundaries with Weather Report and Joni Mitchell.

“And the best bass player before Jaco (in that genre) was Miroslav Vitous,” Hawkins said of Jaco’s predecessor in Weather Report. “He was from Czechoslovakia. I was there when he first landed in New York. This guy came in playing his ass off.”

Spalding, 41, takes jazz bass into a new realm, drawing from her childhood inspiration of seeing cellist Yo-Yo Ma on television and singing in a Portland pop-rock band as a teenager attending the Northwest Academy of Performing Arts. She performed Stevie Wonder’s “Overjoyed” as a salute to the R&B icon in the Obama White House in 2009 and Wonder has supported her ever since. She conveys the etherealness of his best music and adds countermelodies on bass and atmospheric production with modern recording tools.

Her embrace of international influences as a singer fluent in at least three languages and her incorporation of hip hop, such as her collaboration with Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest on “Why We Speak,” makes her one of music’s most multi-dimensional artists.

“She’s a genius,” said Hawkins. “Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, all of these people, that’s already been done. Find something else to do. Spalding, she’s a genius because she’s chosen a way to go that nobody’s done before.”

Hawkins plans to attend Spalding’s festival finale, and he hopes to see Clark on opening night. But he has a busy weekend.

The Idyllwild Arts Academy is celebrating “Dr. Marshall Hawkins Day” Thursday, Feb. 19, in honor of his 40 years at the academy and his long-time leadership of its Jazz in the Pines festival. He’ll perform his annual concert for Black History Month Feb. 21 at the academy.

But, for a guy who has known most of the great bass players of the past 65 years, this Palm Springs International Jazz Festival is a must-see event.

“I hold all that in esteem,” he said. “The bass is the foundation of the music. I don’t care whether it is classical or bluegrass. The bass holds it all down.”

If you go: Palm Springs International Jazz Festival tickets range from $50-$228 each. Information: psjazzfest.org.